Bitcoin as Digital Picassos

One of the easiest and cleverest ways, I reckon, to describe the cryptocurrency phenomenon to neophytes is to liken its remarkable run-up in value to the likewise remarkable run-up in value of Picasso paintings.

Just a couple of months ago, Picasso’s Femme au béret et à la robe quadrillée (Translation: “Woman in beret and checkered dress”) went for $69 million at Sotheby’s. Recent years have seen Gauguins and Cezannes command several hundred million dollars at auction.

“Woman in beret and checkered dress”, Picasso, 1937

What gives a Picasso painting its value, and why $69 million? Most certainly we cannot imagine that the purchaser will personally derive $69 million of hedonic pleasure — beholding the painting, hermit-like, for years on end, happily admitting to the derivation of thousands of dollars per hour of satisfaction.

No, the purchase of the painting has to do with something other than hedonic pleasure: it has do to with status, with the possibility that its increase value will constitute a profitable investment, and, moreover, it has to do with what Karl Menger called “saleableness” — that the painting can be sold on to the next purchaser in due course.

The run-up in value of cryptocurrency can also be thought of in the abovementioned reasons for purchase. Status play a role, as no one wants to miss out on the next big thing, and some like to be seen as anti-establishment. And profit-seeking is likely a main factor, as only a limited supply of some cryptocurrencies will ever be produced. And “saleableness” is perhaps the richest factor with the crypto asset class: we think that we can sell off a digital bearer token, with some ease, at some point in the future, across the artificial boundaries of jurisdiction.

What is conspicuously absent from above, the astute financier might point out, is the admission that bitcoin might actually be useful in and of itself, notwithstanding the fact that hardly anything is valuable in and of itself, and that value depends on the unique human circumstance of time and place.

If you could beam bitcoin across the heavens at warp speed to foreigners, what a revelation that would be! If you could program bitcoin for joint ownership; if you were guaranteed that no more bitcoins would be produced (Picasso is dead; long live Picasso!); and so on. Of course, all the practical matters above are a core reason of what makes bitcoin valuable, and underneath the collectible nature of crypto units is a special use-case: uncensorable digital transactions.

But for the matter of why Picasso is valuable — why bitcoin is valuable — we must look broadly to social as well as technical matters. For example, Picasso was undoubtedly a revolutionary artist. But we can envision some scenario where Picasso’s painting would dramatically decrease in value. These reasons could be either material or social in nature. For example, we can imagine that a new technology to produce undetectable Picasso forgeries is developed. Assuming that the chain of ownership is likewise lost or forged, we can expect this technical discovery to reduce the price of Picassos.

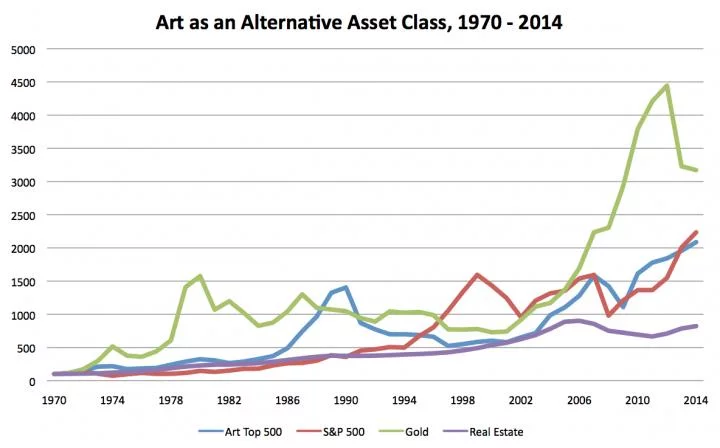

Art and value across time

Decreases in price must not be merely technical or material, of course; we can imagine societal or moral developments which could enervate the aesthetic integrity of a Picasso. New evidence could come out that later Picassos were not in fact painted by the master himself, but by an apprentice. This may drive prices down. And what if it were to come out the Picasso had an evil predilection for kidnap and torture? Do we think that his paintings of outrageous figures would yet command such, well, outrageous figures? Probably not.

The core technology behind cryptocurrency, public key cryptography and hash functions, is very strong. Bitcoin remains heretofore unhacked. But in our joint human endeavor nothing is certain, not even cryptography. Technical hacks would diminish the value of bitcoin. Societal or moral objections are even greater threats. “Moral” objections may come from overzealous regulators who will bemoan cryptocurrency’s possible use in terrorism financing, ransoms, or illicit images involving minors. But other moral pointers out may argue with similar zeal that cryptocurrency will provide benefits, if for example, it is easier to bypass potentially harmful rules against recreational drug use or sex work. Not to mention the potential benefits of personal ownership of data and stronger privacy. We cannot predict the future; and do not know in advance how these new technologies will play out, and what the costs and benefits may be.

In summarry: to tell a person struggling to understand cryptocurrency that cryptocurrency is like a Picasso is to turn the table on the skeptic. Is is to suggest, “You tell me why our communal aesthetic mind does what it does. You tell me why these distorted figures command $69 million. Is it because it is beautiful? Or rare? Or because its stands for the noble savage, the noble rebel? Is it historically important? Is it valuable because others think it is valuable? Is it a grand marketing hoax?” If you can so describe this phenomenon of valuable Picassos to me, which you cannot: it is impossible; then I can describe to you why cryptocurrency is so well-received as well.

May it all blow up into ashes? Yes, it may. But for each passing year that a Picasso commands millions, and a bitcoin commands thousands, the prospect of that collectible item maintaining a similar level of value into the future improves in likelihood. Oh, there are technical benefits too. But consider the Picasso as valuable, and you will come to a better comprehension of the mystery of human action, culture, and subjective value.