Sir Karl Popper and the Unended Quest for the Open Society

Populists through the ages have used rhetoric to its most horrific effects, swapping truths for untruths, discourse for edict, and peace for coercion. Resisting the bully’s dastardly proclivities and undergirding the foundations of a free and open society are those who affirm the principles of democratic free speech, respect for others in the search of truth, and the formal scientific method. One of those intellectuals who resisted the tempting aura of the authoritarianism, central planning, and Fabian socialism in Britain and, to a lesser extent, the United States in the mid-20th Century was the great Austrian philosopher of science, Sir Karl Popper, who was a professor for many years at University College London. Popper stands as a paragon of reasonableness for the 21st Century.

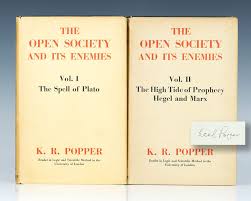

Popper was born in the intellectual hotbed of 1902 Vienna, the melting pot capital of the sprawling, weakening Hapsburg Empire. In that year, Freud would be made a professor, Einstein would first step into the Swiss Patent Office, and Hitler would turn 13. A few decades later, as Popper’s grandfather was Jewish, and as the then-Fuhrer had eyes on Austria, the young academic Karl Popper was employed during the 1930s and World War II years at the University of Canterbury, in far away Christchurch, New Zealand. Here, Popper penned the work for which he is best known, his great critique of Plato, Engels, and Marx, The Open Society and Its Enemies, published in 1945.

The book criticized the great Athenian Plato, who it should be remembered, called for something quite opposite of an open and democratic society. Plato advocated instead for the rule of the state by its rightful guardians, the philosopher-kings. Popper quotes The Republic and the beginning of The Opening Society in a section called “The Spell of Plato”:

The greatest principle of all is that nobody, whether male or female, should ever be without a leader. Nor should the mind of anybody be habituated to letting him do anything at all on his own initiative, neither out of zeal, nor even playfully. But in war and in the midst of peace—to his leader he shall direct his eye and follow him faithfully. And even in the smallest matters he should stand under leadership. For example, he should get up, or move, or wash, or take his means … only if he has been told to do so. . .. In a word, he should teach his soul, by long habit, never to dream of acting independently, and to become utterly incapable of it.

This reminds us of the authoritarian ethos the likes of which two millennia later could be abided by Kaiser Wilhelm or Stalin or Mao. But what is especially poignant about this opening salvo of The Open Society is that it is preceded by an opposing quote, uttered just 80 years earlier, from the defender of democracy, Pericles. Pericles said, “Although only a few may originate a policy, we are all able to judge it.” Popper’s academic thought can be summed up well in two regards by Pericles’ sentiment. Popper thought not just that we can all judge policy and science, but also acknowledged the sad fact that just as we can gain the zest for liberal politics, open discourse, and intellectual freedom, so can we lose it too.

But what makes us revert to the closed society, with all its “alleged innocence and beauty”? For Popper there is a connection between hyper-rationality and authoritarianism. For example, Popper was no fan of history, as he explains in The Open Society. History had no “meaning” he would say. For history, Popper said, had been crafted just so to fit a narrative, a narrative carved by the clerisy from an infinitely large panoply of facts and possibilities. To the resulting splash of happenstance, Popper explained, we cannot meaningfully craft an arc of narrative, though this would not dissuade Engels and Marx. Popper laments “Hegel’s hysterical historicism” and the burdening of past events with undue narrative to fit an authoritarian angle. The commandeering of the past, wrote Popper, could only lead to a commandeering of the present.

And so, in my assessment, stands the first leg of Karl Popper’s two-legged defense of the enlightenment ideal. First, as described, is his vivid description and defense of the Open Society, and his defense of liberal politics from the tribalism that has plagued human affairs since the time of the Greeks, reinforced throught the ages by intellectuals such as Plato, Engels, Marx, and more.

The second leg of Popper’s twofold defense of human freedom was his formal work in the philosophy of science – his admittedly Platonic ideal of the scientific method – called falsification. These two legs, the historical and formal analyses, support each other. Popper said:

[T]he critical method, though it will use tests wherever possible, and preferably practical tests, can be generalized into what I described as the critical or rational attitude. I argue that one of the best sense of “reason” and “reasonableness” was openness to criticism– readiness to be criticized, and eagerness to criticize oneself. (Unended Quest)

Popper said that the scientist or reasonable person must solicit criticism. The reasonable person must always answer this question as specifically as possible: “Under what conditions would I admit that my theory is untenable?” The process of describing these falsifiable criteria, and the very process itself of falsifying hypotheses, for Popper, is science. All else is pseudo-science and thus subject to the commandeering of by politics.

Falsification is a tricky concept to grasp, but might be best understood with a recent example. One real-life example is the bounty placed on the bitcoin network for the proven hash collision of SHA1, offered by Peter Todd. The idea behind a hash function is that it provides a unique digital fingerprint of a piece of data. Each unique piece of data-—e.g. “apple” vs. “@apple” vs. “app!e”-—will have a unique fingerprint that is a few dozen characters long. If it can be proved that “apple” and “@pple” have the same resultant digital fingerprint, then a hash collision is said to be found. And so Todd posited that anyone could claim a bounty of real value (around 2.5 bitcoin) by “demonstrating two messages that are not equal in value, yet result in the same digest when hashed.” [https://bitcointalk.org/index.php?topic=293382.0]. Security researchers discovered a collision, and the bounty was claimed. Bounties still exist for other hash functions used by the bitcoin protocol, such as SHA256 and RIPEMD160.

The SHA1 hash collision bounty is about as pure as possible an implementation of Popperian falsifiability. Not only was the experiment specifically designed to disprove a widely held scientific belief, but also that there was a financial incentive to do so. Most experiments in science will not be so easily contrived as the mathematical certainty of proving a hash collision, where all that is required is that A != B. Nonetheless, scientists should not therefore hide behind a veil of Bayesian skepticism, but should instead undertake the serious effort of experiment design to satisfy the rigorous standards of Popperian falsifiability. Popper respected Einstein because he subjected his theories to this rigrouous test.

Popper would agree with Bayes that science is never proven beyond doubt, nor is consensus science, and tests are the operative unit of science. Science is no grand and gleaming edifice for Popper. Rather, he compares it to piles in a swamp. We are merely trying to stay upright up the swamp of uncertainty below us. He said:

Our ignorance is sobering and boundless … With each step forward, with each problem which we solve, we not only discover new and unsolved problems, but we also discover that where we believed we were standing on firm and safe ground, all things are, in truth, insecure and in a state of flux.

Like Charles Peirce before him, Popper was an eminent fallibilist, a paragon of openness, formal scientific method, and self-awareness. For Popper, error elimination was the name of the game in science, which somehow mimicked his specific psychological outlook and his regard for human psychological tendencies as well. He was no fan of dogma. In this regard he joined in the 1940s a fellow Viennese to have achieved popular intellectual fame while tracing the course of totalitarianism, Freidrich von Hayek. Hayek and Popper stayed close friends for many decades, and were familiar with each others’ work. Hayek even petitioned for Popper’s first academic placement. Both men lampooned logical positivism, the idea that we may deduce from simple facts all that can be known and thus create an optimal world. Both men, hailing from a cosmopolitan Vienna to be overrun by Marxists intellectuals and Nazi soldiers, knew that the world was much messier than logical positvists allowed.

Popper was in favor of a quasi-anarchical system of science, where there was no central authority and ideas stood on their own on trial for the concurrence of peers. Popper was an anti-nationalist, but also was no do-as-you please libertarian. He noted that “Unlimited tolerance,” he said “must lead to the disappearance of tolerance.” He called for rules outlawing intolerance therefore and also for “piecemeal social engineering” (an unfortunate term), which to him meant specific policy interventions, such as those undertaken by the welfare state, subject of course to heavy analysis.

Popper was most of all an academic’s academic. One may be surprised to read in The Open Society his in-depth cross-referencing of ancient Greek texts and the Socratic dialogues. He explored quantum physics, psychology, evolution, and the classics with equal care. Aside from Hayek, Popper early and often had encounters with the most brilliant and creative minds of the 20th Century – the likes of Kurt Godel, Einsten, Wittgenstein, Michael Polanyi, the Mises brothers, and E.M. Gombrich – dot Popper’s intellectual autobiography, Unended Quest. He taught George Soros, Imre Lakatos, and Paul Feyerabend, There was the time in Princeton when Popper tried to convince Einstein to give up his belief that the world was deterministic, “ a four-dimensional Parminidean block universe in which change was a human illusion (or very nearly so).” (See: Parmenides). There was also the time in London when an outraged Ludwig Wittgenstein angrily wielded a fire poker when a young Popper deftly critiqued his Tracticus.

Popper lived long enough to celebrate the fall of the Soviet Union as, along with the buildup to World War I, one of the most consequential courses of events of his life. He called for the abolition of nuclear weapons. He was saddened in the 1990s that “the propaganda that we live in an ugly world” had succeeded. He claimed instead that we in fact live in the best time since humankind’s birth, a time where the unquestioned myths of the nation, the tribe, relgion, and tradition have yielded ground to steady scientific persuasion. He was a great optimist. “We must go on into the unknown, the uncertain, and insecure, he said, “using what reason we may have to plan as well as we can for both security and freedom.”