Steven Stoll's 'Ramp Hollow: The Ordeal of Appalachia' review, and some thoughts on Marxist historicism

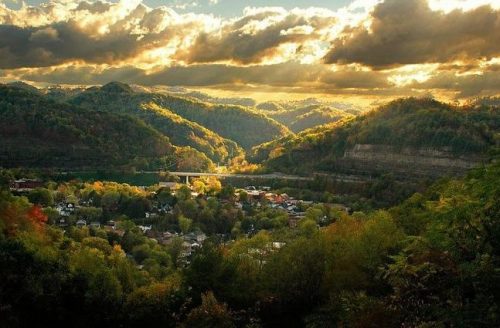

It’s evident from reading Ramp Hollow: The Ordeal of Appalachia by Fordham University history professor Steven Stoll that Prof. Stoll cares deeply about Appalachia. Stoll writes with great empathy about the gentle slopes and shade and colorful personalities found yonder. His book, published a couple years ago, explains how the “household mode of production” of the West Virginia smallholder—plot farming, a few livestock nibbling on the underbrush, selling what little surplus you yielded—was cut short by timber companies then Big Coal in the denouement of a Great American Tragedy.

Stoll’s book laments the dispossession of the land by the vagaries of short-sighted capitalists. It calls for a renaissance and newfound respect for the smallholder, the peasant, the campesino, those who forage, farm, and hunt on land they own or share in tacit neighborly agreement. This way of living off the land, Stoll suggests, is not only native to West Virginia. Stoll recounts how the English peasants were smallholders too in common pastures; that is, until the pastures were fenced off and claimed by the barons and lords. The Native Americans too had their livelihoods and land stolen, and now, Stoll says, it’s happening to the Africans. For all our praise of the onward progress of capitalist modes of production and consumption, Stoll takes care to point out, we miss the fact that maybe these peasants aren’t such helpless antediluvians after all. Rather, they are interacting sustainably with nature, unlike the capitalists. What’s more they are able to provide for themselves just fine, thank you, if only the centralizing forces of government and Big Coal would kindly quit sticking their noses in their neck of the woods.

Indeed it wasn’t just the capitalist designs of Big Coal that made West Virginia one of the poorest states in America and killed off the mountain man, says Stoll. It was also the centralizing forces of government. Consider the Whiskey Rebellion of 1791-1794. Whiskey, with its anesthetizing properties and long shelf-life, was important as a medium of exchange to Appalachian smallholders. Alexander Hamilton’s Department of Treasury decided to tax whiskey. To Stoll, it wasn’t just the financial aspect of the tax that is notable. It’s that the G-men effectively mounted a hostile takeover over the Appalachian region in a maneuver to bring the purported force of progress and centralized governance to the unwitting Westerners, with all its associated taxes, ledgers, and debt. Maybe the Appalchians should have been left alone.

So goes Stoll’s story. Stoll’s book tells these historical anecdotes with flourish, but it doesn’t stick to the script promised of the subtitle of the book. He doesn’t explain the “Ordeal of Appalachia” in any detailed or comprehensive manner. Tell me, what specifically were the proceses by which the West Virginians were dispossesed? Stoll jumps from one Marxist interpretation from the next, forgetting that the reader expects him to give historical facts, not ex post sociological conjecture. The more significant critique of his book is that it’s not readily evident that the last two hundred years of Appalachian history have, on the whole, even been an ordeal. Yes, West Virginia today is wretchedly poor in comparison with other states. But Prof. Stoll does not wish to consider that impoverished smallholders in 1920, who may have starved in the winter of 1919, might have wanted to voluntarily sell their plots to a coal company and move to California. Stoll mentions in passing that since 1952, the population of West Virginia has decreased by 40%. This, on the same time frame where the population of Texas increased by 350%. Good for Texas. And good for the 40% (or more, taking into account natural population growth) who left West Virginia. How are they and their children and grandchildren are faring now, in, say, Houston and L.A.? Any honest history of a people must also consider their descendants, wherever they roam.

Stoll, the progressive that he is, has an undue appreciation for the occupations of the poor of the past. Who wants to forage anymore? And well, yes, coal mining is a dirty and dangerous job. But Stoll doesn’t consider that some might even prefer to work a pick ax in a mine than a spade in a field. Neither is nice, by the standards of 2018, and manual labor is not glorious. Stoll doesn’t mention that refrigeration, electric lighting, and antibiotics mattered most for the poor. Try getting a root canal in with tools from 1880, then we can talk about the joys of foraging. It is the surplus afforded by speclialization of labor that has allowed us to invest and innovate and improve the lot of humankind. And finally, and I cannot know for sure, but I would guess that in West Virginia in 2018 it is more pleasant than in 1918 to be a woman, divorced, Jewish, gay, or black. More West Virginians today have more choices than ever before to live the life they want to live, instead of the life that their father used to make them live, often enforced by violence.

“One of the basic insights of political ecology,” Stoll claims at one point, “is that poverty is not the lack of things that people had never known but a social relation in which people are deprived of the means of subsistence.” (pg. 256) No. The reduction of poverty, in fact, is caused precisely by the invention of things “that people had never had known.” It’s called innovation, a word that appears not once in Prof. Stoll’s deeply pessimistic book. So long as we take care with our words, so that “subsistence” means what it typically means (“maintaining or supporting oneself at a minimum level,” says Merriam-Webster) then we can confidently say that subsistence is at an all-time high and that poverty—everywhere—an all-time low, even for the sorry folk of West Virginia. Poverty is not a “social relation” as the Marxists would have it, but an absolute state. Having clean water, not being crippled by polio, being able to get books and play guitars—these things are now more abundant in West Virginia than ever before. Contra Marx and Stoll, neither coal, nor labor, nor land, nor resources made happen this great enrichment of all humankind. Of course, they all played a role. But on the whole, it was the liberation of the human mind from the ancient trammels of ignorance and deference to father, king, and clergy. This is the liberation that created “things that people had never known,” and we are better, materially and spiritually, for it.

Now, I wouldn’t pass Prof. Stoll’s midterm by pointing out to him that he has missed the forest of innovation for the fossilized tree. Stoll might argue in response that, “Sure we are much richer, but this does not change the fact that capitalism exploits people. Look at who got rich off of coal, the elite, the wielders of capital.” Well, yes, Mr. Peabody got rich off coal. But should we really care that the baron of the manor gets his third gold bracelet or that the coal baron gets his third gold Rolex? Quit with this fascination with the tiny sliver of the richest. You, dear reader, by the very act of reading this essay, understand that the most valuable things in life come cheaply. Give the coal baron his third Rolex and give the masses of the poor their first running faucet. The trade works better for the poor.

Stoll would have more objections. Look to the squalid slums outside major cities, he says. “If the corporations pursuing their objectives through free trade over the last one hundred years really spread wealth wherever they went, there would be no Global Slum of 1 billion people.” (pg. 287) Stoll, for being a proponent of self-sufficiency and individualism, sure doesn’t sound like it sometimes. Maybe the poor want to live close to the cities because there is opportunity there, if not for them then for their children. If the options are either live in a slum in the village or a slum near the city, many will choose the city. Even the poor can choose where to live and where to work, and by so doing, improve their lot. And furthermore, the evidence of a bad thing does not mean that a good thing is not working. No one claims that creative destruction benefits everyone at all times, “destruction” being the one of the two words. There are indeed losers from free trade. But as the economic historian Deirdre McCloskey puts it: “That even over the long run there remain some poor people does not mean the system is not working for the poor, so long as their condition is continuing to improve, as it is, and so long as the percentage of the desperately poor is heading toward zero, as it is. That people still sometimes die in hospitals does not mean that medicine is to be replaced by witch doctors.”

Stoll would advocate bringing in the witch doctors to make economic policy. He often lapses into senseless oversimplification such as “when people take care of landscapes, landscapes take care of them.” Tell that to the potato farmer in Ireland in 1841. Or else Marxist topsy-turvyism like “When people buy and sell commodities, they appear to but working for their own betterment even if they are really satisfying the imperatives set by others.” (pg. 64) Thank you, Professor, and when I next buy my morning coffee, I will remember that I am really doing the bidding of Starbucks. It just seems ironic that the New York socialist professor should exclaim, “Hands off our agrarian tradition!” as he does. Stoll’s vision is a pathetic vision of the wage-earning poor, in the Greek sense, as though the gods have forsaken them, but not as they have personal agency to improve themselves. Stoll suggests that one of the “unsettling currents” in J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy is that Vance suggests Appalchians might have to move to improve their lot. Reality is often unsettling; sometimes it warrants settling somewhere else, as the Appalachain ancestors did when they sailed across the cold Atlantic in creaking wooden ships.

Typical for the Marxist, Stoll plays fast and loose with the word “capital.” Stoll notes that people “who lack government protection” are “subject to capital” (pg. 286), as though “capital” is a masked intruder in the night and “government” the saving force. The phrase “subject to capital” isn’t even meaningful. Who isn’t “subject to capital”? For Marxists like Stoll or Terry Eagleton or Thomas Piketty, “capital” an elusive catch-all, a straw man, and a scapegoat all at once. Marxists treat capital as if it is some vile goo, not comprehending that capital comes in countless forms, that any business investment is fraught with anxious risk, and that all companies can, have, and will go bankrupt in the face of annoying competition and ever-changing demand. We should feel for the tragedy of the poor says the Marxist scholar like Stoll, trying to stake the moral high ground. He is right; we should. But electricity companies hardly felt for the poor, and yet electricity for the masses—powered probably by coal—helped the poor enormously, more than, say, any Marxist scholar or high-minded do-gooder ever could.

West Virginia is but one small place, and coal miners but one small profession. We cannot extrapolate from this sorry case more general lessons of exploitation. The trouble with thinking about West Virginia is that the environmental and social costs can be so clearly laid upon this small population in this small place, while the benefits of its economic harvest, namely cheap electricity for the masses, are so thinly spread and taken for granted. But coal-as-power was once an incredible innovation. Coal and oil were worthless and dirty until someone realized they could be burned for heating, lighting, mechanical energy, and electric applicances. It took thousands of human brains working together to extract coal, not just Mr. Moneybags and some brute force. As a political issue, free trade faces a similar challenge: the losers can be identified, but the winners cannot. And if a leftist populist like Bernie Sanders, not a rightist populist like Donald Trump, were calling for a repeal of NAFTA, Prof. Stoll might be first to register his support. For a learned man like Stoll, who evidently likes a good yarn, it is hard to appreciate that the economy cannot be made into a story and consequently that the countless interactions that comprise the extended order of free enterprise are best left to their own devices.

Stoll is his strongest when considering that the centralized rulemaking, especially when tainted by the corruption, bribery and nepotism of public officials, can work against the goals of the common man. Stoll is right to note that the story of economic growth is not all there is. Not all of economic activity can be captured by the filthy lucre. Even such accepted economic conceptions as “employment” and “unemployment” are not applicable for the smallholder. Should household production, childcare, or volunteer work count as employment? The ways that people can interact economically are diverse, and we should not prize the moneyed type over another type. The centralizing features of Hamilton should be counterbalanced by the decentralized tendencies of Jefferson. And of course Stoll’s point that an economic monoculture makes for an unsteady economy is well-taken.

But even Stoll’s choice of historical evidence is shaky. His claims about enclosure in England, such as that it led to “starvation and poverty” (pg. 48), are plain wrong. Population increased after enclosure, and so did crop yields. And at root, what caused the involuntary dispossession of the English peasant or the West Virginia smallholder? Was it the relentless drive for the ever-elusive scapegoat in Marxist thought—capital!—or was it something more banal, perhaps a few quid or dollars placed in a few of the right palms around Westminster or Charleston? I am suggesting that the dimensions of fences mattered very much indeed from a distribution of wealth in England, just as whoever owned the coal mines got rich, at least in the first act. But splitting up a tiny pie is still a tiny pie whether it’s England in 1800 or West Virginia in 1900. And all got rich in the second and third act. Dispossession offends our sensibilities, as it should; it is despicable to see someone cheated by the law or to see union-breaking scabs beating the tar out of a poor miner. But that there is corruption, regrettably, always and everywhere, is not cause to reexamine the fundamental principles of liberty that have gotten us to the levels of unprecedented wealth and comfort that we enjoy today.

Unlike Prof. Stoll, I must admit, I do not care so much about Appalachia, not West Virginia or Kentucky. Nor do I care about Canada or China. I do care about the people of these places, insofar as they are domiciled there at any given time. When they move and their jobs change, my concerns move along with them. This is first mistake Stoll-qua-conservative makes: the mistake of wanting to fossilize in place a way of life, when the people on the ground may want something entirely different. The second mistake is that of Stoll-qua-progressive, the mistake that Karl Popper calls “historicism.” It is the tendency of the Marxist historian to want to form out of the infinite splash of historical happenstance some meaningful narrative, with a clear and defined personae dramatis. It is an easy and very human thing to want to do. But Stoll excoriates one historicist and foolish grand theory, that of The Great Law of Economic Progress, while proffering his own, that of The Exploitation of the Rural Poor. Both stories are wrong. The real story is the expansion of choice and scope offered to the common person and the unpredictable innovation that has arisen from this opportunity. Let the people have a go. Insofar as we can expand the possibility of the choices that even the lowly West Virginian has, we are on the right track.